Introduction

First, the good news: a GP’s middle years, say from age 35 to age 55, are typified by high incomes.

Alas, they are also typified by even higher living costs! Indeed, these are “the peak-cost years”.

Sometimes the peak-cost years make it simply too hard to do any significant investing. Family goals come first and this is fine. The kids are kids for such a short time that it is foolhardy to sacrifice the desired family lifestyle for investing. There is plenty of time to get the investments going later once the kids are off mum and dad’s hands. After all, GPs retire much later than everyone else, anyway.

It can seem that no matter how hard the GP works and how much cash comes in, the cash goes out faster. Cash consumption exceeds disposable cash income at all levels of disposable cash income. There are a virtually infinite number of claims on the family budget. The money just goes. Sometimes it seems investing is just a pipe dream, just another thing that might happen one day – if the kids let you.

Some GPs, probably less than a third, invest significantly during the peak-cost years. They tend to be those who have invested well in the earlier years, and, in particular, those who bought homes and paid off their home loans as soon as possible. This has freed up a lot of their cash flow such that they can meet the significant expense of raising teenagers while still having (even a little) left over.

But most GPs are not able to do much fresh investing in the peak-cost years.

In summary, there is not enough money.

Take a typical male GP called, say, Fred, age 43. Fred bought into the practice last year for $120,000 and the practice premises for $150,000, using debt secured against their home (value $1,200,000 with $600,000 of remaining home loan).

Total assets are $2,000,000 with $970,000 of loans.

These will be good investments, but they will struggle with the loans for years to come.

Fred’s wife Wilma works four days a week and the combined before tax family income, including rents, is $350,000 a year. This is divided between Fred $270,000 and Wilma $80,000 (both including super and car fringe benefits). Fred’s after tax income is about $195,000 and Wilma’s after tax income is about $65,000. This means the family has about $260,000 cash available to it.

Fred and Wilma have three kids. The eldest two are in their secondary years at a private school, and the youngest one is at a state public school.

Let’s look at the family’s annual cash payments budget:

| Home loan principal and interest payments on $600,000 | $60,000 |

| Investment loan principal payments on $270,000 | $30,000 |

| Superannuation contributions | $50,000 |

| School fees and related costs | $50,000 |

| Two cars | $20,000 |

| Food | $40,000 |

| Clothes | $20,000 |

| Entertainment and holidays | $15,000 |

| Rates, repairs and maintenance and so on | $5,000 |

| Total Cash Costs | $286,000 |

You do not need to be a CPA to see the problem. Cash costs of $286,000 are greater than available cash of $260,000. There is a shortfall of more than $26,000 cash each year, or about $500 cash a week.

This shortfall may surprise you, but it is normal for most middle-aged GPs with families.

The solution is to work harder and longer and/or spend less. But this does not really help: new costs present and what’s saved somewhere is quickly spent elsewhere.

The real problem is that it costs at least $250,000 cash a year to live a normal slightly upper middle class) lifestyle, pay off the home loan and pay some extra into super.

Cash costs tend to exceed cash income at all levels of cash income. This is a normal problem. So is the stress that comes with it.

GPs who invested well earlier avoid this problem, and the stress that comes with it.

Obviously if a GP has followed our advice and bought as much home as possible as early as possible, got the tax planning right, developed their practice as a business (and enjoyed at least an extra $100,000 a year every year) and started to invest excess cash in other investments then their financial prospects are better in these peak cost years.

In fact, some GPs invest so well earlier they are insulated from the financial rigors of family responsibilities, and go on adding to their net wealth each year. All the good family stuff is enjoyed while at the same time the family’s financial fortunes get better and better.

A common advice

We often find ourselves explaining that the peak cost years are a normal financial phenomena and that do not last forever. GPs do not need to do anything drastic. The peak cost years will pass. There will be plenty of time to build wealth later. The family’s immediate priorities should prevail.

The key is to:

- own a home in a fashionable suburb, or soon to be fashionable suburb, that rise in value at a rate greater than the average home;

- keep up the super contributions, ideally at the maximum allowed each year, so that you are in the top 1% of savers;

- look after your health; and

- enjoy yourself and your family lifestyle.

The growth in the home’s value and the super accounts are creating a firm financial base, and you do not have to do much more, for now at least.

Should you borrow to pay for the peak cost years?

Ideally you will not borrow to pay for the peak cost years.

But sometimes there is no choice. For example, what if Dr Fred in our example above had another child, and a fourth lot of school fees, and Wilma could not work for a salary: she was too busy maintaining the home, particularly with Dr Fred working such long hours?

This is, of course, a common presentation.

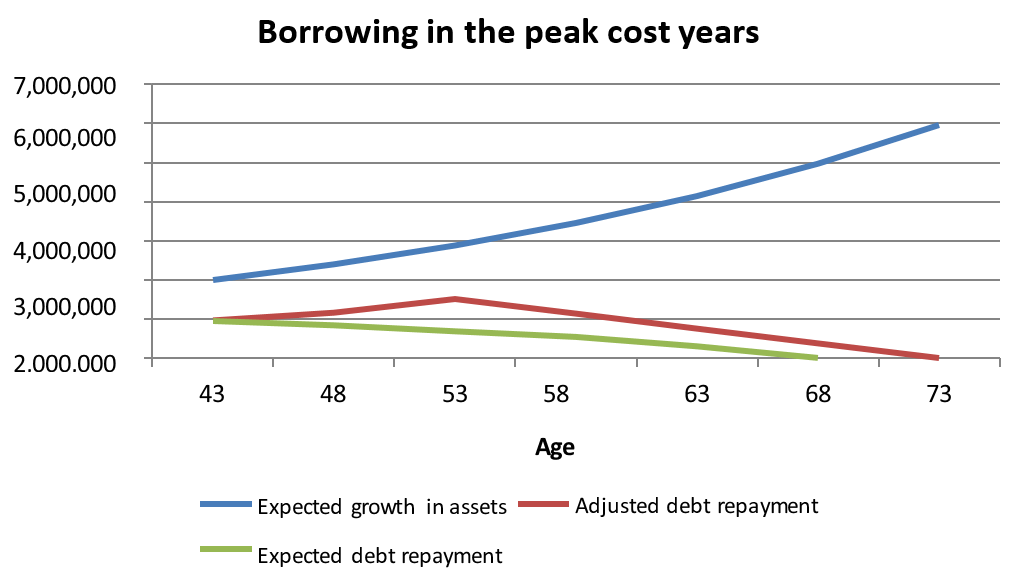

It can make sense to borrow to fund the peak cost years. The position can be graphed like this:

Fred and Wilma have about $2,000,000 in assets now, and about $1,000,000 in debt. If they don’t borrow any more and continue the expected debt repayment plan (green line) they will pay off their loans at age 68.

If Fred and Wilma decide to borrow to help pay their peak costs they move to the adjusted debt repayment plan (red line) and will pay off their loans at age 73.

Fred and Wilma can relax a bit financially, borrow to pay for school fees and family holidays, and still achieve their family goals, very confident that once the peak cost years pass there is plenty of time and opportunity to build the assets up.

Most men at Fred’s age of 43 have only 15 years left in the workforce. But Fred at age 43 can keep working on a high income for even another 30 years. Arguably, he has a life’s work ahead of him (if he wants it). The height, stability, scalability and longevity of Fred’s income make borrowing in the peak cost years a sensible financial strategy.

Financial planning for divorcees

Up to one third of marriages end in divorce. It’s more for GPs, probably reflecting the stress and long hours away from home and hearth.

It’s normal for a newly divorced GP around age 50 to be bereft of assets, worried about the future and feeling that, financially at least, being a GP is not all it was cracked up to be.

The good news is that if you are going to be relatively bereft of assets and worried about the future being a GP is great occupation to be in. Most fifty year olds face seriously uncertain financial futures. There is an age prejudice and a youth bias in many workplaces. Retrenchment is a real prospect and, for most workers, retrenchment means forced retirement, with no second chance to establish a firm financial base.

Not so for GPs.

There is a shortage of GPs and experienced GPs, divorced or not, can take their pick of practices and work almost wherever they want whenever they want. There is no age prejudice or youth bias in general practice.

So, the solution for a newly divorced GP, age circa 50, with few assets is simple. It boils down to:

- keep working. But do so at a pace and in a space you are comfortable with. The idea is to keep working as long as you can, but on a progressively reducing basis until, say, age 75 (or whatever age you – and your patients! – are comfortable with). That means you have 20 more years to build up wealth and that’s more than enough time;

- paying the maximum super contributions each year, ideally on a monthly basis using automatic Over two decades this will grow to be a very sizable sum, more than enough to get you through to a comfortable retirement;

- buying a It does not have to be a four bedroomed four-car garage mansion. Think small. A three bedroom townhouse is all you need, and this comes at up to half the price of a larger house;

- using a GP friendly lender so you can borrow more than otherwise, and then pay off that expensive non-deductible loan as fast as you can (using an interest offset account). Rapid non-deductible debt reduction is the key to getting ahead at all ages, and age 50 is no exception;

- having appropriate income protection insurance in place, but do not over-insure;

- potentially investing in a medical practice: most owners make an extra $100,000 or more a year, and this is the safest and least risky way for a GP to build up new wealth;

- tax planning, including making sure you get the best structure for your

Over the years we have seen countless GPs down on their luck at age 50 achieve financial success by age 60. Once again, it’s all down to the characteristics of a GP’s income. Its height, stability, scalability and longevity mean, GPs recover financially from divorce a lot faster than most people.

It’s part of being a GP. It is the payback for all the hard work you have done so far.